Over the previous academic year, I completed my Master’s project at UCL, and during this time I have thought quite a bit about what makes such a short project successful. To be clear, when I say successful, what I have in mind is that the student has learned new skills and managed to create a standalone well-rounded piece of work. Note that this may not be the same as getting a good mark or being able to publish your work, however, usually these things go together. The most important transferable skills one can gain during a Master’s project are those related to experimental design, data analysis and scientific writing. (These are also exactly the kind of skills that will make you a desirable applicant to PhD programmes.) It is easy to see how the acquisition of these skills is directly related to the number of experiments one can perform.

Essentially, the more experiments you have, the more times you can go back to the drawing board and rethink your approach. Similarly, the more experiments you perform, the more data you will be able to analyze and report on. The actual subject of your work matters very little in this case (it’s unlikely to be revolutionary anyway), what matters is the number of high-quality experimental results you can obtain. In this blog post, I will discuss how one can maximize the amount of such experimental results by (I) choosing the right model system and (II) incorporating data from published work.

Busy Master’s student. Made with https://www.bing.com/images/create.

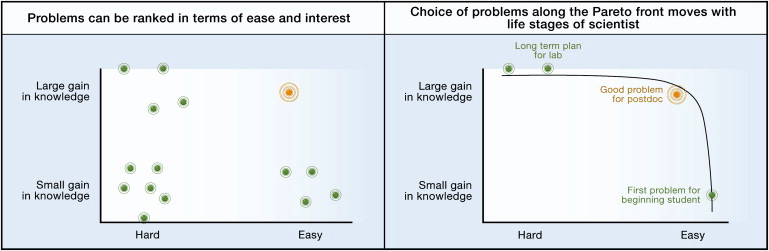

I initially started thinking about these questions after having read Uri Alon’s paper How to Choose a Good Scientific Problem (which is well worth reading). In it, he has a diagram illustrating that the difficulty of a project and the knowledge gained from it shows an obvious trade-off, such that a project that uncovers more knowledge is generally more difficult. He argues, that different combinations of difficulty and discovery might present suitable project options depending on the stage of one’s career. Easy projects, which probably won’t discover a cure for Alzheimer’s, are still fitting for early career researchers, whereas complex problems are suitable for a long-term vision of an entire lab. Here I introduce a third (somewhat independent) axis to Alon’s way of thinking, which is the rate at which one can do experiments. This is crucial because everyone working in a lab is limited by time, either because they will eventually graduate, or because their fixed-term employment/fellowship is over. As such, it is also crucial to consider whether a project can accumulate results fast enough.

“Two axes for choosing scientific problems: feasibility and interest.” Source: Uri Alon: How to Choose a Good Scientific Problem. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.09.013.

As I said, the main focus of a short project is not to discover something revolutionary but to pick up useful skills as a young scientist. So one can pretty much ignore the “Gain in knowledge” axis and only consider difficulty. However, for a Master’s student who has 6-12 months in a lab, it is not enough for a scientific problem to be easy. They will also need to be able to maximize experimental data collection in this short timeframe. At the extreme, consider someone trying to study whether a certain drug makes mice live longer. This is in principle a very easy question, with a relatively simple experimental design which I will leave to the reader. But given that mice live for about 3 years long, this is already impossible to answer within a Master’s project. Now imagine, you are doing the same experiment on fruit flies (3 months), worms (3 weeks) or yeast cells (3 days), which will allow you to perform at least 4, 14 or 122 experiments respectively. (These will also give you less and less exciting results, but as I said, revolutionary findings are not the point anyway.)

Additionally, even an experiment that takes two weeks, does not truly require two weeks of complete attention, and usually, multiple such experiments can be run in parallel. So the maximum number of experiments one can perform in a given timeframe depends on two things: how long an experiment takes, and how many experiments can be done in parallel.

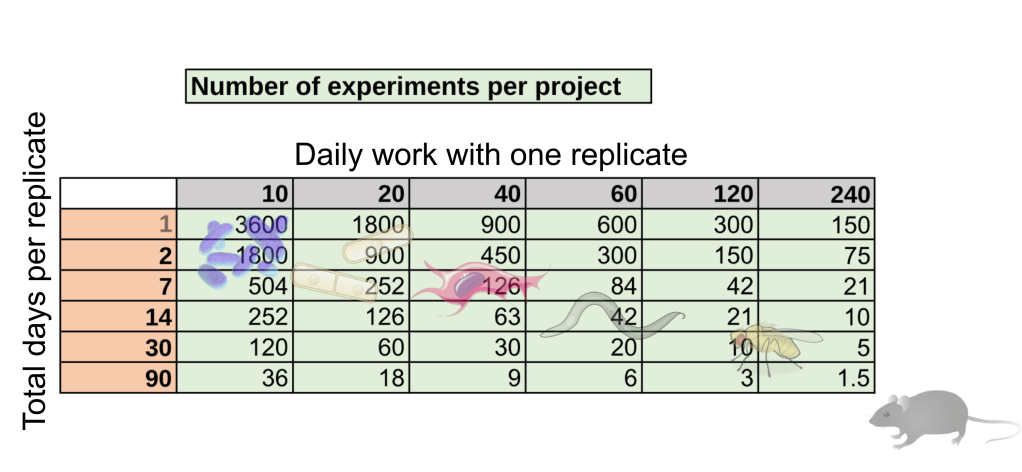

We can assume 300 working days with 4 hours dedicated to experiments each day. Further, let’s be optimistic and assume that half of the experiments will work and provide useful data. We obtain the following number of successful experiments:

Table 1.: Number of experiments in a 12-month project, assuming 300 working days with 4 hours dedicated to experiments each day and a 50% success rate. Depending on Daily work (minutes) and Total days per replicate, one can calculate the maximum number of successful experiments. Images of organisms mark different experimental regimes, but obviously, these strongly depend on your scientific problem and approach as well.

We can immediately see that working on a system where experiments can be done both rapidly and in a highly parallel manner will allow one to obtain orders of magnitude more data compared to someone working on time-consuming experiments. As I have already mentioned, this depends entirely on the model system one works on, and specifically on its rate of cell growth (e.g., a flask of E. coli grows up overnight, while mouse embryonic development, let alone aging, takes long). This broadly speaking creates the following hierarchy:

E. coli > Yeast > human cells (fibroblasts, cancer lines etc.) > worms > flies > stem cells > mice

It was based on this simple logic that I chose to work on yeast for my Master’s project (also using lots of E. coli for various molecular biology reasons). For context, in my project I worked on the genetics of multicellularity in fission yeast cells. (To be exact, for various reasons it is not actually “true multicellularity”, and we termed it multicellular-like phenotypes.) Generally, yeast cells take 2 days to be grown after being taken out from the freezer, and it took another 4 days to grow 96 such strains in a very specific arrangement, after which we could assay them (in about 2 minutes) for adhesion. My daily tasks involved maybe on average 5 minutes with an experimental replicate of this sort. This simple experimental setup with code-automated analysis allowed me to assay various yeast libraries, including a genome-wide deletion collection. Then I was able to find both environmental conditions and gene mutations that trigger the formation of multicellular-like phenotypes. When I read or found something interesting, I could immediately go back to the drawing board, propose a new experiment, and get the results in a week. This is all because my project took place in the upper left corner of Table 1.

Me during my project (Or at least how I remember a year later). Made with https://www.bing.com/images/create.

Others in my department weren’t so lucky, and had projects in the lower right corner of Table 1. These were projects in which they counted the number flies or worms alive throughout the lifetime of an entire population. These took 4-6 hours daily, and experiments lasted 3 weeks or 3 months, for worms and flies respectively. Needless to say, such projects are much more risky, because if things go wrong (e.g., contamination, expired chemicals), one might end up with barely any useful data to analyze. And indeed, many people I know who did similar projects had trouble finding anything interesting.

Some of the other students in my department. (Or at least how I saw them.) Made with https://www.bing.com/images/create.

Conclusion 1: Choose your model system wisely. The more experiments you can do the better.

However, one is still limited in the amount of data they can gather on their own in 12 months. Therefore a great way to further increase the amount of data in your project is to incorporate results from published work. Suppose you find an interesting gene in your project, and you wish you could perform RNA-seq or proteomics to further explore what happens when that specific gene is deleted or perturbed in some way. Well, there might already be such data available! People perform experiments for many different projects, perhaps completely unrelated to what you are interested in, and therefore you could still discover something interesting using their data. Additionally, in the case of model organisms, like fission yeast, there are lots of large-scale experiments which generate vast amounts of data exactly for this purpose, to be used by other people.

As an example, I found that phosphate starvation in fission yeast results in formation of multicellular-like phenotypes. Of course, there was a recently published RNA-seq dataset of fission yeast under phosphate starvation, and guess what I found, that cell adhesion genes were indeed upregulated. As another example, I also found the deletion of the gene srb11 to cause multicellular-like phenotype formation. Luckily there was microarray data available from deletion of genes that function together with srb11. Interestingly they all upregulated cell adhesion proteins, through a pathway we suspected already.

The point is that performing experiments like RNA-seq are expensive and require time. However, if you can just incorporate such data from external sources, your project will benefit a great deal. And it does not matter at all that you did not collect that data, so long as you can incorporate it in your project in a unique way.

There is lots of publicly available data to explore! Made with https://www.bing.com/images/create.

Conclusion 2: Look for external datasets that you can use in your project. This provides you with much more information, while saving you time and money.

To wrap up, we can consider the relationship between the amount of experimental data and project progress. We can reasonably assume an exponential relationship. In this framework, accumulating more data eventually leads to getting more “bang for your buck”. At given levels of progression, we can visualize milestones, such as reaching sufficient statistical power, finding something meaningful, building a story, and at the very end, reaching a publishable level. My claim is that if you choose your model system wisely, and smartly incorporate other people’s work, then eventually you will get more and more out of it. (E.g., once you’ve incorporated external data properly, your next experiments are more likely to show something interesting. Or the other way around, if you performed good experiments, external data might further strengthen your argument.) You will reach important milestones in your project much faster, and much easier, while others will run out of time, and hand-in substandard work. So what’s the best decision you can make to have a successful short project?

Exponential curve showing one’s progress in a project as experimental data is gathered. A bad project will run out of time before reaching important milestones. A good project will allow for lots of experimentation and use of external data, and will complete all milestones in time.

Conclusion 3: Go work on yeast!

If you are interested in how the project I was part of turned out, you can now read our pre-print on Biorxiv! (I will probably write a blog post on this as well.)

https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2023.12.15.571870v2

Additionally, thinking about this made me realise that most of microbiology should/could be repurposed to serve an educational goal for young scientists, especially because microbiology is losing funding and in general becoming less relevant (partly due to the explosion of good human models). So expect something on this in the future as well.

In the meantime, if you found any of this interesting, get in touch.